Canarypwn’s Blog [index]

Canarypwn’s Blog [index]

This is the blog of canarypwn. I am a Ph.D. student at North Carolina State University. Here I write about various topics including programming, technology, and personal experiences. Stay tuned for updates!

Articles

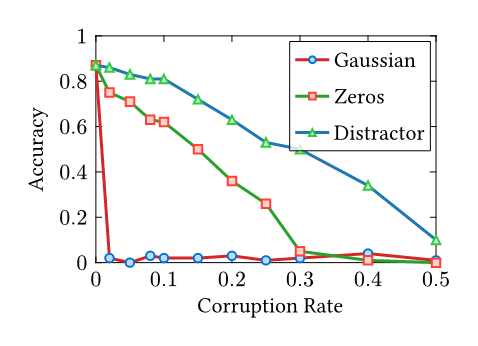

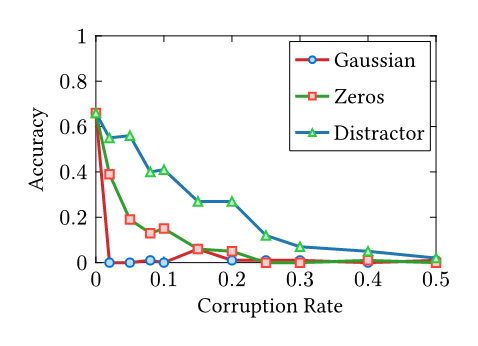

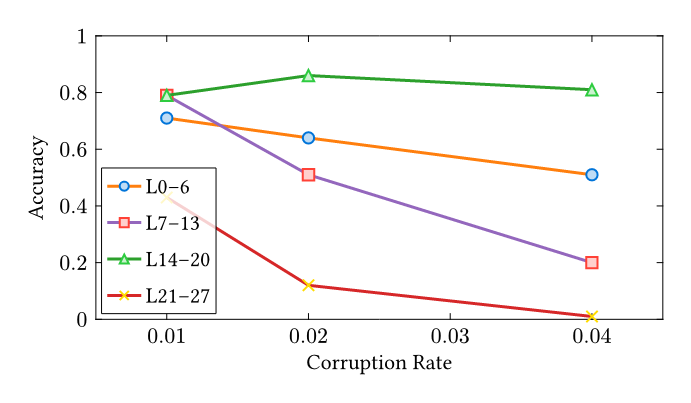

Recently, I have been researching bug reproduction in SGLang and vLLM. During my bug hunting, I encountered an intriguing issue: SGLang#17839 (archive). Two aspects of this issue caught my interest. First, the Many works in our community leverage open-source models to evaluate coding ability, and during rebuttals, reviewers often ask, “What if you switch to an open-source model?” My question is: How can you trust a model that fails at grade-school math? While I am not an expert in LLM evaluation and acknowledge that methodology is often more important than the model choice itself, I strongly suggest using the best model available unless you precisely understand your model’s behavior. The second aspect relates to the bug itself. Briefly, when using a legal but misconfigured SGLang setup, the model’s KV Cache (its context memory) becomes corrupted in the computer memory—specifically, the address pointers of the KV cache point to incorrect locations. Common sense suggests the LLM should fail to output anything meaningful, as the next token generated depends strictly on the preceding sequence. If the KV cache is scrambled, the dependency chain is broken. However, the evaluation results still showed a surprisingly high 75% accuracy. A severe infrastructure bug that scrambles the model’s entire context memory, yet barely dents the final answers. I formed a hypothesis: humans can ignore noise in language context—for example, ignoring irrelevant conditions in “trap” exam questions. Do LLMs possess a similar ability to ignore noise within their internal KV Cache? While there is extensive research on prompt injection and KV cache compression, my investigation offers a different angle. As Anthropic noted in a postmortem of their own inference bugs, “Claude often recovers well from isolated mistakes”—standard evaluations simply failed to surface the degradation [1]. This resilience is exactly what I set out to measure. All results and source code are open-sourced at Nyovelt/Internal-Robustness. Most of the code was implemented by Claude Code, as the logic is straightforward. As someone who deals with the vLLM KV cache daily, I briefly examined the code to ensure the method for modifying the KV cache was technically sound. The rationale is simple: I systematically corrupt the KV cache with different noise types (Gaussian Noise, Zeros, Unrelated Prompts) and evaluate the performance on the For each corruption rate \(r \in [0, 1]\), I randomly select \(r \times 100\%\) of the KV cache entries during autoregressive decoding and replace them with the chosen noise type. Each experiment uses 100 samples from the GSM8K test split, with greedy decoding and a maximum of 512 new tokens. For the layer-sensitivity analysis, I divide the 28-layer The research questions are: Results Analysis: Random Noise Sensitivity: For unstructured random noise (Gaussian), replacing just 2% of the KV Cache results in severe accuracy degradation. Both the 7B and 1.5B models collapse at the same 2% Gaussian cliff. Likely, the attention mechanism cannot ignore values that look nothing like real data. Each corrupted step compounds into the next, and within a few tokens, the output becomes pure hallucination. Structured Noise Robustness: For structured noise (like zeros or distractors), the model is significantly more robust. This is consistent with the behavior observed in the SGLang bug: even when replacing 30% of the KV cache with completely different content in the 7B model, it retains 50% accuracy. A possible explanation is that these “distractor” KV pairs remain within the distribution of training data—they look like real activations. The attention mechanism was trained specifically to focus on relevant context and suppress irrelevant context. It is doing exactly what it learned to do: filtering signal from noise. To test whether certain layers are more critical than others, I divided the 28 layers of It resembles a factory assembly line. Disrupting the final quality-control station (late layers) ruins everything. Disrupting a middle packaging step (L14–20) barely matters because other steps compensate. Disrupting the raw material intake (early layers) causes moderate problems. Both the 7B and 1.5B models collapse at the same 2% Gaussian cliff. Scale does not buy resilience against out-of-distribution corruption. However, the 7B model is more resilient against structured noise (zeros, distractors)—more parameters mean more redundancy for in-distribution filtering. 1. KV Cache is More Robust Than You Think in Large Language Models [kv-cache-robustness]

Introduction

gpt-oss model (the 120b variant) only achieves 85% accuracy on the gsm8k benchmark. For readers unfamiliar with gsm8k, it is a standard evaluation dataset consisting of grade-school math problems, such as “64 cookies for 16 people, how many cookies does each person get?” It is hard to imagine a SoTA open-source model in mid-2025 struggling with a significant fraction of these questions.Methodology

gsm8k benchmark. I used two older but differently sized models: Qwen2.5-1.5B-Instruct and Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct.Qwen2.5-7B into four quarters (L0–6, L7–13, L14–20, L21–27) and two halves (L0–13, L14–27), corrupting only the selected band at three rates around the cliff point (\(r \in \{0.01, 0.02, 0.04\}\)).

Evaluation

Noise-type Comparison

Corruption Rate

7B Gaussian

7B Zeros

7B Distractor

1.5B Gaussian

1.5B Zeros

1.5B Distractor

0.00 (baseline)

0.87

0.87

0.87

0.66

0.66

0.66

0.02

0.02

0.75

0.86

0.00

0.39

0.55

0.05

0.00

0.71

0.83

0.00

0.19

0.56

0.08

0.03

0.63

0.81

0.01

0.13

0.40

0.10

0.02

0.62

0.81

0.00

0.15

0.41

0.15

0.02

0.50

0.72

0.06

0.06

0.27

0.20

0.03

0.36

0.63

0.01

0.05

0.27

0.25

0.01

0.26

0.53

0.01

0.00

0.12

0.30

0.02

0.05

0.50

0.01

0.00

0.07

0.40

0.04

0.01

0.34

0.00

0.01

0.05

0.50

0.01

0.00

0.10

0.01

0.00

0.02

Not All Layers Are Equal

Qwen2.5-7B into four quarters and two halves, corrupting only the selected band with Gaussian noise at three rates near the cliff point.

Layer Band

\(r = 0.01\)

\(r = 0.02\)

\(r = 0.04\)

L0–6 (early)

0.71

0.64

0.51

L7–13

0.79

0.51

0.20

L14–20 (buffer)

0.79

0.86

0.81

L21–27 (late)

0.43

0.12

0.01

L0–13 (first half)

0.44

0.10

0.04

L14–27 (second half)

0.34

0.04

0.01

Bigger Models Are Not Tougher Against Random Noise

Takeaways

Qwen2.5-7B. Layers 14–20 appear to be a “buffer zone” with high redundancy—a potential target for future pruning or efficiency research.